Ballimaran in Its Infinite Labyrinth of Turmoil

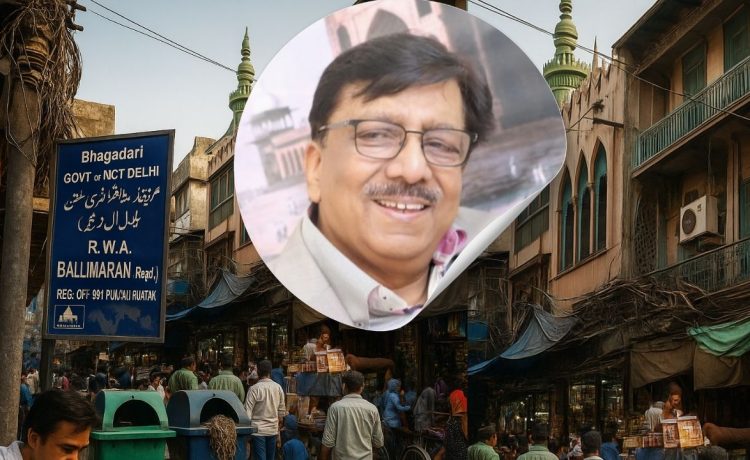

An excerpt from Shahid Siddiqui’s memoir on culture, society, and politics

The Partition and Old Delhi’s Divides

In the years following Partition, Old Delhi — today known as Delhi-6 — bore invisible borders. Hindu and Muslim families often lived in separate sections of the same narrow lanes. Among them stood Haveli Hesamuddin in Ballimaran, the mohalla (locality) of a prosperous Muslim business community called the Shamsi baradari.

Though colloquially referred to as Punjabi Phatak (Punjabi Gate), these residents were not Punjabis in the true sense. They had migrated from Central Asia, fair-skinned with blue eyes and blond hair, and spoke no Punjabi. Many among them owned flourishing businesses in Chandni Chowk and Sadar Bazar, as well as large showrooms, hotels, and palatial homes in Connaught Place, Kashmiri Gate, and Civil Lines — then Delhi’s most exclusive residential area.

For Shahid Siddiqui’s family, who were not part of this community, life came with suspicion. The government allotted them a house vacated by a Muslim family that had migrated to Pakistan.

A Neighbourhood in Transition

By the 1950s, Ballimaran was undergoing rapid change. Prominent families had left for Pakistan, while others from different parts of India were drawn to the area. It became a hub of post-Partition Muslim politics, culture, and intellectual revival.

The mohalla carried the legacy of Mirza Ghalib, and with freedom fighter and journalist Hasrat Mohani spending his final years there, Ballimaran soon turned into a gathering place for writers, poets, revolutionaries, and activists. Figures like Kuldip Nayar, Josh Malihabadi, Habib Tanvir, and Baba Niaz Haider found refuge in its havelis and lanes.

Birth of Nai Duniya

In 1951, Siddiqui’s father resigned from the Aljamiat and launched a new daily newspaper, Nai Duniya, from Haveli Hesamuddin. The ground floor was converted into the newsroom, while the upper floors, with large rooms and sprawling terraces, became a sanctuary for intellectuals, activists, and artists.

The atmosphere was electric. Plays were rehearsed on one terrace, while mushairas (poetic symposiums) unfolded on another. Communist leaders debated politics in one room, while ulema discussed relief work in another. Writers, artists, and thinkers — from M.F. Husain and Gulzar to Zubair Rizvi — mingled freely.

The terraces were lined with cots (charpai or khat), where anyone could sleep, sip tea, and eat nahari-roti. For Siddiqui as a child, these interactions created a vibrant world of “cultural cocktails” and revolutionary ideas.

Sarla Gupta’s Unlikely Victory

In 1952, Ballimaran witnessed a political surprise. Sarla Gupta, a young woman from a prominent Delhi family, decided to contest the municipal corporation elections on a Communist Party of India ticket. Fresh out of Delhi University, she sought to transform society.

It seemed impossible: a young woman, a communist, running in a predominantly Muslim constituency. Yet with Siddiqui’s father backing her campaign, she defeated the Congress candidate. The victory was not only symbolic — it became the first post-Partition election win in the area.

Fear, Suspicion, and Politics

For many Muslims, the Indian National Congress was seen as the only reliable protector after Independence. Even those critical of leaders like Nehru, Patel, and Azad continued to vote for Congress. Parties like the Hindu Mahasabha and the newly-formed Bharatiya Jana Sangh (BJS) were viewed with fear and suspicion.

A third-party candidate was often dismissed as vote katwa (vote divider), potentially helping right-wing Hindu groups gain ground. This fear was heightened after Sarla Gupta’s win.

Congress leaders grew uneasy, while others — including Uttar Pradesh’s first Chief Minister, Govind Ballabh Pant — saw communists as dangerous. Right-wing organizations exaggerated the victory, portraying it as a Muslim-Communist conspiracy to take over India’s politics.

A Community at Crossroads

For Indian Muslims, still reeling from Partition and the migration of many community leaders to Pakistan, this was a period of profound uncertainty. They struggled to find representation and a voice in India’s democracy.

As Siddiqui recalls, democracy seemed to many Muslims like a system meant for the Hindu majority, not for them. Ballimaran, with its tangled lanes and turbulent politics, symbolized both their hope and disillusionment in independent India.

📖 Excerpted with permission from I, Witness by Shahid Siddiqui (Rupa Publications).

📌 Background & Context

-

Ballimaran is a historic locality in Old Delhi, famously home to Mirza Ghalib. After Partition (1947), it became a melting pot of cultures, politics, and refugees.

-

Many wealthy Muslim traders (Shamsi Baradari) left for Pakistan, leaving behind havelis that became spaces for intellectual, political, and cultural activity.

-

Shahid Siddiqui’s memoir captures how his father launched the daily Nai Duniya (1951) from Haveli Hesamuddin, turning it into a hub for poets, revolutionaries, artists, and activists.

-

In 1952, Sarla Gupta, a young woman from Delhi, won the municipal elections from Ballimaran on a Communist ticket — defeating Congress. This shook the political establishment and reflected Muslims’ post-Partition anxieties.

-

The memoir shows how Muslims negotiated identity, survival, and politics in the fragile years after Partition.

📌 Key Quotes

On Ballimaran’s diversity:

“In those tangled lanes, Muslims and Hindus lived side by side, yet invisible borders of Partition still divided us.” – Shahid Siddiqui

On Nai Duniya’s role:

“The newspaper office was more than a workplace. It became a refuge for poets, activists, and dreamers — a laboratory of ideas.” – Shahid Siddiqui

On cultural life:

“On one terrace, mushairas would echo into the night; on another, communists debated Nehru’s policies; in a room nearby, ulema discussed relief work for riot victims.” – Shahid Siddiqui

On Muslim politics post-Partition:

“For Muslims, democracy often felt like a system meant for the majority. Congress was seen as their only shield, while others were viewed with suspicion.” – Shahid Siddiqui

On Sarla Gupta’s win:

“It was unthinkable for a young woman, a communist, to win from a Muslim seat. Yet Ballimaran made it possible — a victory that unsettled the Congress and alarmed the right wing.” – Shahid Siddiqui

![]()