India’s demographic dividend will remain incomplete unless policy decisively shifts from welfare-driven approaches to women-led economic growth

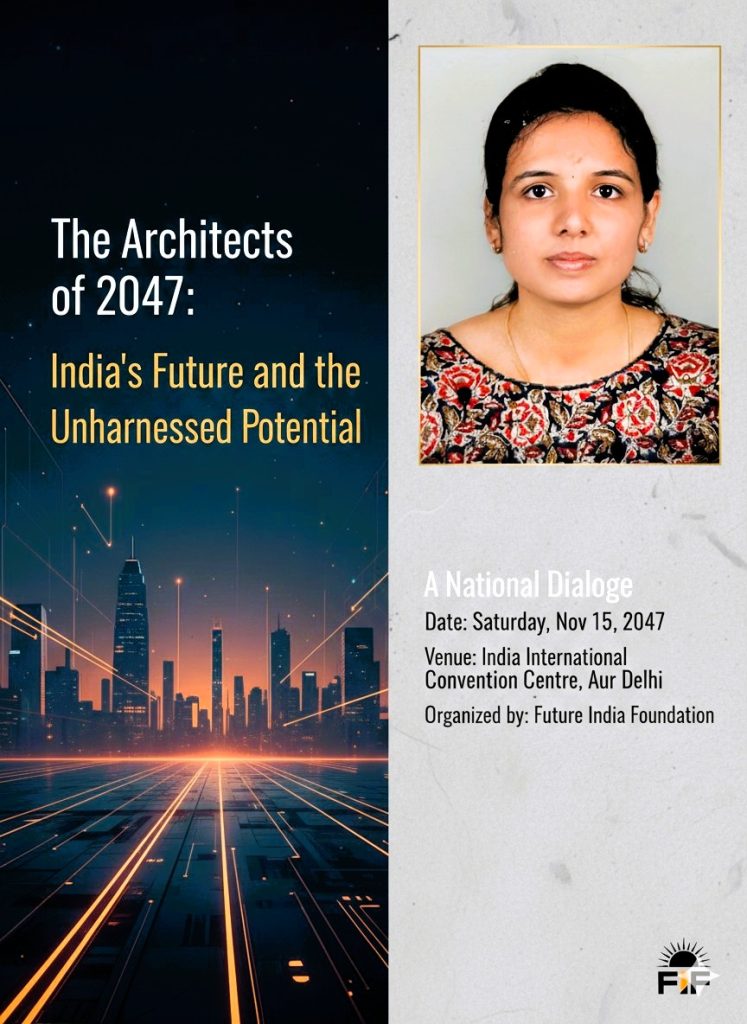

By Dr. Haritha V H

By 2030, India’s working-age population—those between 15 and 59 years—is projected to cross 98 crore, marking a demographic peak that many nations never experience. Yet, as the Economic Survey 2025–26 underlines, numbers alone do not create prosperity. The true dividend lies in how productively this workforce is employed. In that equation, India’s vast pool of women remains its most underutilised asset—and its greatest opportunity on the road to Viksit Bharat 2047.

A Stark Educational Gap

Despite steady progress in enrolment, advanced education among working women remains alarmingly low. Barely three out of every 100 working women in India hold postgraduate or higher qualifications. In an economy aspiring to become a developed nation by 2047, such a figure cannot remain an exception; it must become the norm.

The Economic Survey makes a pointed observation: demographic advantage must be matched with structural transformation. For India, this transformation cannot occur without systematically integrating women into high-productivity sectors that define modern growth.

From Welfare to Women-Led Growth

A significant shift is now visible in policy thinking—from viewing women primarily through a welfare lens to recognising them as drivers of economic expansion. This change is expected to reflect in the upcoming Union Budget, with a sharper focus on enabling women’s participation in manufacturing, technology, and emerging industries.

As the Survey argues, growth dividends are realised when labour moves from low-productivity activities to high-value sectors. For millions of women currently concentrated in informal and agrarian roles, this transition will require deliberate fiscal and institutional support.

Bridging the Skills Divide

At the heart of this transition lies a skills gap, particularly in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM). Budgetary support for targeted STEM scholarships, advanced training programmes, and vocational hubs could radically alter the current landscape. Such measures would not only improve employability but also create a pipeline of women professionals capable of driving innovation and high-end manufacturing.

“Empowerment,” as policymakers increasingly acknowledge, “is not merely about access—it is about capability and opportunity.” Translating that recognition into sustained investment will determine whether India’s female workforce becomes a growth engine or remains an untapped reserve.

Safety, Mobility, and the Urban Question

Economic participation is inseparable from physical security. For women migrating to cities for work, safe and affordable housing remains a critical barrier. Expanded funding for initiatives such as Tamil Nadu’s Thozhi Hostels and the national Sakhi Niwas programme could significantly ease this constraint, enabling women to seek and sustain urban employment.

Equally important is workplace flexibility. Incentivising firms to institutionalise flexible and hybrid work models can unlock a vast pool of educated, home-bound women whose skills remain underutilised due to rigid employment structures.

For Media Updates: +91-93531 21474 [WhatsApp]

Beyond Budget Arithmetic

Ultimately, the Union Budget must be more than a ledger of revenues and expenditures. It must serve as a statement of national intent. If India is serious about its aspiration to become a $30-trillion economy, it cannot rely on infrastructure and innovation alone.

The success of Viksit Bharat 2047 will depend on whether India fully harnesses the strength, skill, and ambition of its women. The architects of India’s future are already here. The question is whether policy will finally give them the tools to build it.

![]()